FOSStering Education

Contents

- Why FOSS makes sense in education

- What's up with Indian EdTech?

- The case against proprietary software in education

- FOSStering Education

- Policy Implications

- The Kerala Model

- Challenges to FOSS adoption

- FOSS United

Why FOSS makes sense in education

Education is one of the key long-term focus areas of FOSS United. It is pragmatic in the sense that promoting and strengthening the Indian FOSS ecosystem also means making sure the next generation is more aware of Free and Open Source Software. I've come to realise that educational institutions are going to be key players in evangelising FOSS in India, so I decided to spend the last few weeks pondering why they should be doing so. This is my case on why FOSS makes sense in education and what are some good reasons for FOSS implementation in Education Technology (or its notorious short-form EdTech).

For the purpose of this post, 'Education Sector' refers to formal education institutions in India - schools (govt. and private), colleges, and universities - where adoption of technology is shaped by policy, procurement and public funding.

What's up with Indian EdTech?

The COVID-19 pandemic brought drastic changes to the Indian education system. Online classes became a thing overnight and institutions had to move to whatever digital alternatives were available to continue teaching students. The number of EdTech users in India doubled from 45 million in 2019 to 90 million in 2020. After all it has been through, the sector is still projected to contribute 0.4% of the GDP and achieve a valuation 29 bn $ by 2030, with over 100 mn paid users.

All of this has led to a wide access gap because of the uneven and rapid adoption of technology. While a small amount of the student population reaped the benefits of the EdTech innovations, a significant majority could not keep up because of their socio-economic backgrounds.

Despite all innovation, our education system continues to suffer from systemic challenges around fair access to education, the inability to afford educational material and tools, students dropping out at early ages and a lack of employment even among the educated.

While India has the capability to create software to help improve the lives of people around the world, its citizens do not have the capability to absorb it. One main reason is that India does not have a good infrastructure. In addition, the economic conditions do not allow our citizens in general, and students in particular to buy expensive hardware and software. Lack of good quality educational institutions and good teachers compound the problem.

-Kannan M. Moudgalya, Campaign for IT literacy through FOSS and Spoken Tutorials,SCIPY 2014

The case against proprietary software in education

The problems with proprietary software span across domains. In the education sector, tangible problems associated with non FOSS solutions are -

Cost

Obviously, these solutions are expensive. A major portion of an educational institution's budget goes towards recurring license fees to these services. This financial burden diverts funds from other critical needs. In an already tense environment where education is expensive while teachers are underpaid, these costs are a huge danger.

There are 634924 upper primary and secondary schools in India. If each school spends Rs 1.3 lakhs on software, the total spending will be Rs 8254 crores. All the proprietary software can be entirely replaced by FOSS and just that could result in a potential saving of Rs 8254 crores for the country as a whole.

Do note that the National ICT Policy of India recommends the adoption of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) to mitigate such costs.

Lock-ins

The entire business models of big tech products revolve around keeping you locked in to the ecosystem. Education is no different. Educational institutes are forced to purchase recurring licenses to proprietary products year on year since they don't have the option to switch to another product.

Proprietary ecosystems also force teachers and students to adapt to their specific learning environments which hinders creativity and further reduces teacher agency in a system where education is already very rigid and stresses on "sticking to the syllabus". This was evident during COVID when institutes regularly struggled to figure out how they can scale their educational tools (hint: by paying more money!).

Privacy

The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 requires Indian drug manufacturers to publish all the ingredients of their drugs on the product label. What is a mandatory requirement for drugs is for some reason considered a weakness when we demand it for software that can have impact on millions! Proprietary software in Education is a black-box drug with all sorts of serious side effects, and yet we continue to use it.

Student privacy is a serious problem to consider when opting for an educational platform. Massive data collection, lack of transparency, absolute control over student data raise ethical concerns with using proprietary software. More often than not these platforms also have very poor security practices. The Unacademy Data Breach, reports on Zoom app exploiting facial recognition technology without prior permission from the users are famous examples.(I'm not even going to talk about the hundreds of YouTube videos on "Zoombombing" classes!)

These are just few of the problems with proprietary ecosystems. Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam emphasized this point in a speech 22 years ago after meeting Bill Gates-

“I would like to narrate an event that took place in Rashtrapati Bhavan a few months back when I met Bill Gates, the CEO of Microsoft. While walking in the Mughal garden, we were discussing the future challenges in Information Technology including the issues related to software security. I made a point that we look for open source codes so that we can easily introduce the users built security algorithms. Our discussions became difficult since our views were different. The most unfortunate thing is that India still seems to believe in proprietary solutions. Further spread of IT which is influencing the daily life of individuals would have a devastating effect on the lives of society due to any small shift in the business practice involving these proprietory solutions. It is precisely for these reasons open source software need to be built which would be cost effective for the entire society. In India, open source code software will have to come and stay in a big way for the benefit of our billion people.”

-Address at the Dedication Function at International Institute of Information Technology

FOSStering education

FOSS is built on the principles of freedom, collaboration, community, equality and accessibility. Like education, FOSS also values ethics over profit and is not driven by commercial goals. It is precisely for these reasons why FOSS makes sense in education.

Good outcomes can only be achieved by working in the open. In college, students are told to speak at conferences, publish their work and findings etc. While these may seem like things you are told to do for improving your CV today, the goal is much more nuanced. In that sense, FOSS and academia have very similar and idealistic goals.

One can argue that FOSS is in fact an implementation of this "working in the open" approach of academia. It's not uncommon for academicians to publish algorithms which are then picked up and implemented by engineers. A lot of popular FOSS projects have their roots in academia - Linux and GIMP both were research projects that started out as part of the authors' coursework.

My point is that to some extent, FOSS is just a way of implementing and creating meaningful discussion around academic concepts. It gives students the opportunity to solve real world problems and learn real world skills through collaboration that just can't be gained from normal educational settings. It introduces them to the principles of humanities and community learning whilst doing what they love, programming!

Wikipedia allows users all over the world to collaborate on and edit information. Similarly, students need to be able to collaborate as part of the learning process. Our education system has become overly outcome oriented, and mistakes are not an option. The goal of education, shouldn't be to produce correct outcomes (even Wikipedia has inaccuracies!), but debuggable (fixable) ones, hence "free and open".

Policy Implications

Policy, if implemented correctly can have huge impacts on the FOSS ecosystem in India. FOSS adoption in the Indian education sector is still in its infancy. While policy in this regards exists, there is a huge gap in its implementation.

The Policy on the adoption of open source software for the Government of India (2015) is an effort to increase OSS adoption in government organisations. It states that all things being equal, preference will be given to FOSS. While it exists, there are major gaps in this policy's implementation. This is primarily because of the "all things being equal" and "urgent/strategic needs" exceptions in the document which makes it easy for these organisations to opt for proprietary software (and for vendors to fool employees into purchasing expensive licenses!).

In 2005, the government of India, in cooperation with the Department of Information Technology (DIT) and the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT) established the National Resource Centre for Free/Open Source Software (NRCFOSS). The mission of this agency is to provide resources to FOSS-related projects in the country.

The Economic Impact of Usage of FOSS in Government found that just schools replacing all proprietary software with FOSS and could result in a potential saving of Rs 8254 crores for the country as a whole. FOSS can be made mandatory for schools.

FOSS can be made mandatory for schools. This study shows that ICT concepts can be taught with FOSS tools, and FOSS can be used to teach other subjects also.

The National Education Policy (2020) can act as a fundamental bridge for FOSS advoacy in education. While there are multiple sections in the NEP that perfectly align with FOSS values, it is disappointing that the policy does not mention Free and Open Source Software explicitly.

The NEP implicitly accepts that such materials must be accessible to all, without the constraints of traditional copyright (‘all rights reserved’ by the author/publisher). However, it does not explicitly call for the creation of ‘Open Educational Resources’ (OER). Any content is OER if it is licensed using ‘copyleft’ or ‘creative commons’ licensing, which allows others to re-use, revise, curate, and re-distribute the content.

Likewise, although the NEP recommends that a variety of educational software applications should be developed and made available in Indian languages, it stops short of calling for the licensing of such software through the “general public license” which is the popular license used by free software communities to develop and distribute free and open-source software (FOSS). FOSS and OER licensing make software and content ‘public’ resources that everyone can participate in creating, using, and sharing. Thus, the call in the NEP to invest in the creation of open, inter-operable, evolvable, public digital infrastructure in the education sector must be read as necessarily including FOSS, OER, open hardware and connectivity, as well as open standards in each of these.

As far as effects of policy are concerned, Kerala is the only (and very successful) state that has implemented large scale FOSS adoption through policy. The Education department of Kerala adopted FOSS for all government schools in support of a state policy that recommended FOSS for all government departments and offices. (2001)

Most states, other than Kerala have opted for and continue to implement proprietary software.

Karnataka

FOSS was not encouraged by either the state or the vendors. Some NGOs in Karnataka, such as IT for Change, worked extensively with schools and the education department to spread awareness and understanding of FOSS. However, the state relied on the vendors and did not permit use or installation of FOSS.

Some schools in and around Bangalore received computers from philanthropic grants with FOSS installed on them. For the most part these were later replaced with proprietary software.

The syllabus for computer subjects was developed by the vendors according to the guidelines provided by the Department of Education. For the most part, the syllabus and the content was tailored by the vendors. The syllabi for other subjects, such as Science and Mathematics, was left to the schools and teachers, to develop lesson plans using the software already installed by the vendors.

The field interviews showed that there was no attempt to train or inform teachers or department personnel about FOSS. The vendors actively discouraged use of FOSS, and downplayed its value and usefulness. One of the department officals remarked:

When we procured the systems, we paid for Windows. If we go for Open Source, then everything we paid for is waste.

Goa

In the year 2000, an NGO in Goa, called the Goa Schools Computer Project,undertook an effort to procure old computers from corporations and distribute them in schools. The NGO was able to give computers to 380 schools,in which FOSS had been preloaded. The costs of such a deployment were very low, and the main challenge they faced was that of training teachers. However, initial training was provided and teachers felt comfortable using FOSS and teaching with the available software. This attempt did not survive, as the government stepped in later to provide computers to schools and the task was outsourced.

Maharashtra

Most teachers received training. All government new hires were required to take a six month course on information technology. This was necessary for teachers also. The training was outsourced and the vendors taught only Windows and proprietary software. Some teachers mentioned using Geogebra in class, but they learnt this on their own. They were not aware that Geogebra is open source.

A convener on the board of studies for ICT stated that he was worried about recommending open source for fear of being questioned. He had no such worries about recommending proprietary software.

Assam

The software used by the vendors was entirely proprietary. In 2009, Assam government did recommend use of FOSS in the curriculum but this was not implemented. In part this was because the state government had already signed a ‘partners in learning’ memorandum with Microsoft corporation, who would provide software and learning tools under the scheme, at special prices.

For the ICT subjects, the entire syllabus, teaching materials and also the exams were prepared by the vendors. The materials were designed with approval from the competent authority in the state (the education department).

Assam Electronics Development Corporation (AMTRON) has actively followed a policy of promoting and highlighting FOSS in the syllabus and for training. However, the vendors follow this only reluctantly. Linux training was provided in a few schools.

The Kerala model

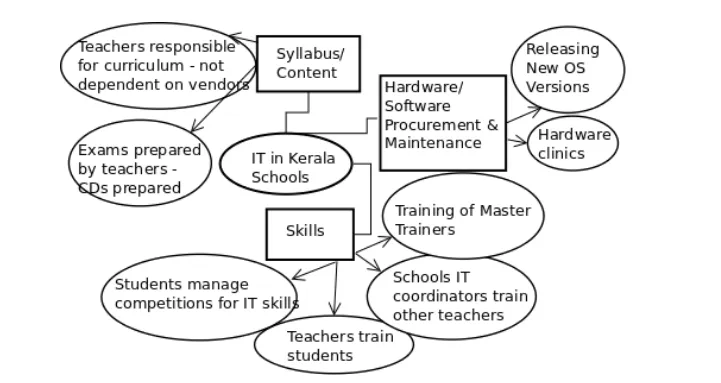

The KITE / IT@School Project (2001)

Source:Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC)

We briefly touched upon the Kerala state government's efforts to introduce FOSS, better known as the IT@School project (now rebranded to KITE). Please refer to the IIMB report mentioned earlier for detailed insights.

The IT@School Project is the single largest simultaneous deployment of FOSS based Information and Communication Technology (ICT) education in the world. The Education department adopted FOSS for all government schools in support of a state policy in 2001, using their own resources! They prepared a Linux distribution that was installed on computers. It included other FOSS educational packages, such as Geogebra, Kalzium that could be used to teach different subjects.

This shift has led to a rethinking of the educational system from ground up, with FOSS becoming a given whenever adopting a new solution. The effects of these FOSS implementations reap their benefits even today, and the population has become a heavy FOSS consumer and proponent.

Hardware procurement was centralised with a state vendor responsible for delivery and maintenance. However, schools became proficient at maintaining the hardware themselves and didn't need to rely on vendors basic issues like upgrading drivers. After the warranty period was over, hardware clinics were set up to help people fix each other's problems, further upskilling teachers and students.

As a result of all of this, unlike other states teachers in Kerala became involved in the curriculum development. They were able to give inputs on syllabus and design tests as they'd like.

This high level of participation is also a function of the use of FOSS, which has fostered a culture of involvement and sharing, thus creating a community. Teachers actively contribute to blogs and wikis on their subject. They feel involved and committed to their work, and don’t leave it to vendors to design and structure the instructional material.

Teacher agency is only possible when there is FOSS.

-Gurumurthy Kasinathan, Director, IT for Change

These changes are saving the Kerala government upwards of 300 crores every year, and promote a DIY/hacker culture among the students from a very early age.

Source:Reddit

Challenges to FOSS adoption

While FOSS may be a tangible solution to a lot of problems in our education ecosystem, pitching for its adoption is not easy. Thanks to decades of lobbying, the ecosystem is ridden with vendors. Institutes are neither familiar with FOSS, nor have the confidence and interest in changing decisions. People in the system that do know of FOSS have lots of misconceptions, which are often created by the vendors themselves in an effort to brainwash teachers.

Some felt that FOSS was more expensive than proprietary software, including the cost of licenses. Some responded by saying that FOSS created a lock-in, because once they adopt FOSS, they would be unable to select any other (they also felt that proprietary and monopoly software like Windows did not create such a lock-in). The other doubts expressed about FOSS included - FOSS was not reliable; FOSS was prone to virus attacks; was unstable; did not have vendor support; and was harder to maintain.

Capacity building is required before putting in efforts for large scale FOSS implementation. Most people within the system (who are technically responsible for taking the decisions) have no idea why a particular piece of software was chosen, this is usually left upon the vendor to decide. Teachers also believe technology is inferior to traditional teaching methods, which is why interventions are not considered a priority.

Besides, our highly rigid technical educational system does not provide the right environment for tinkering and hacking. The capital-rich Indian tech industry hardly spends any into FOSS projects. Hence, we say the issue is both systemic and cultural.

With educators and students not exposed to the ideas and usage of FOSS from an early stage education, it becomes difficult to change these habits at a later stage. In many cases, the syllabus explicitly specifies proprietary software brand names (such as MSWord, MSExcel) instead of using generic terms like documents, spreadsheet, giving teachers and students no freedom to choose the software that meets their needs.

-State of FOSS in India, Civic Data Lab

FOSS United

I've put a lot of thought into where does FOSS United fit into this equation. It's taken me a lot of time to understand what does it really take to strengthen India's FOSS ecosystem.

I used to think FOSS United was basically YCombinator for FOSS startups out of India. The goal would be to scout for projects with value, help them with funding, build meaningful bridges that help them scale and connect project creators with the right people. This definition serves its purpose for the most part, but something was missing. How does any of this enable creation of FOSS? Unlike entrepreneurship, FOSS has a long way to go in terms of promotion and awareness.

This is where education comes in. FOSS can act as an enabler to overcome all of the challenges that we've discussed before.

The education sector is fertile ground to enable an organic cycle of FOSS usage and equally important value adoption, to inculcate larger ideas of contribution back to the community.

Setting up FOSS Clubs in college campuses is only the beginning. Only 5.5% of engineers in India today have basic programming skills, and most of the technology graduates out of college can't write a working program. If every engineering campus had a community that was open to all, promoted a tinkering and hacker culture, helped students talk to people with real experience we'd eventually create a system where better engineers come out of India.

This really was the last piece of the puzzle for me. Large scale technology adoption is a step ahead towards an equitable education. FOSS can help make this journey easier for the 30 crore students of India. Once the right culture has been set in place, we will see good quality FOSS projects coming out of campuses. Once you graduate out of college, there will be multiple FOSS companies and startups that enable you to follow your passion while ensuring a good livelihood, and joining MNCs will not be the only way ahead. There will be enough risk capital in the ecosystem for people to build FOSS products from India for the world, and we'd have built an ecosystem that is truly "free and open".

This blog post is an extended version of my talk at Critical Studies for Education and Technology, 2025 organised by IT for Change.

Thanks to Sai Rahul Poruri, Shobhankita Reddy, Shree Kumar and Chandra for reading early drafts and sharing feedback - their comments helped a lot in shaping this post!

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License